Dr. Barry Popkin and Dr. Shu Wen Ng believe that, with the right policy actions, many low- and middle-income countries can still avoid reaching the high levels of ultra-processed food intake and nutrition-related diseases currently faced by many countries around the world. In a recent article in Obesity Reviews, Popkin and Ng outline why countries should commit now to policies that can improve or strengthen dietary choices and social norms around food, before ultra-processed products overtake their food systems.

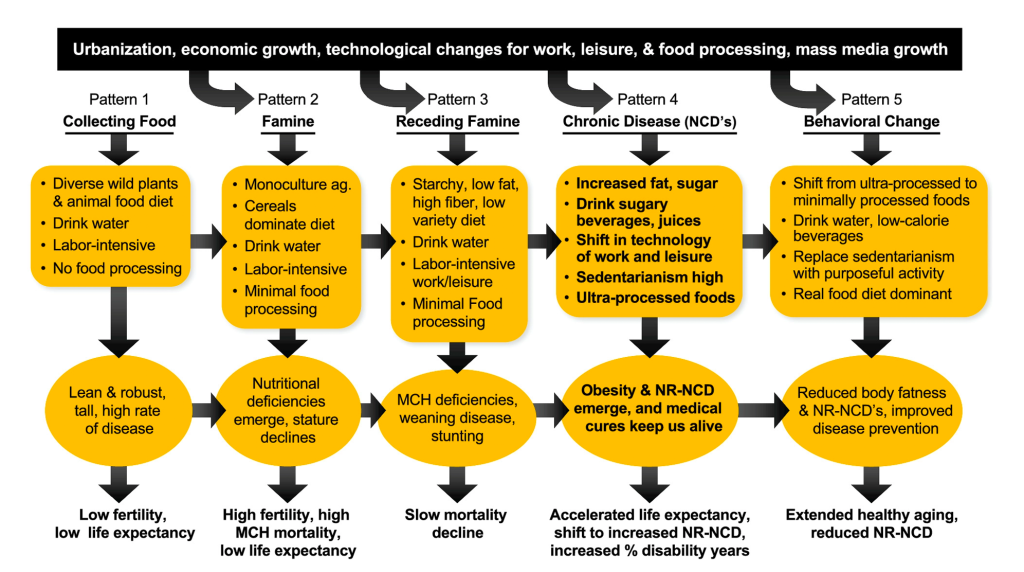

The authors describe countries’ current dietary, physical activity, and epidemiological trends within the Nutrition Transition, a model first put forward by Popkin in the 1990s. The Nutrition Transition describes a series of five dietary patterns and associated health outcomes that have occurred — or are currently occurring — as populations shift from hunter-gathering through periods of famine, receding famine, increasing consumption of processed foods, and ideally, a shift back to consuming a diet of mostly real, minimally processed foods.

AUTHORS:

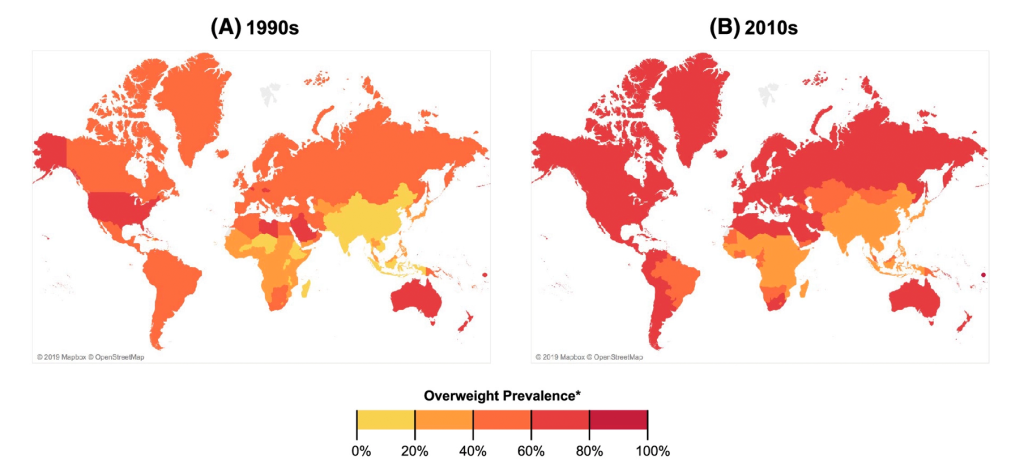

Today, virtually all high-income, many middle-income, and some low-income countries are experiencing Pattern 4 of the Nutrition Transition. Ultra-processed foods and drinks make up anywhere from 20–60% of the diet, physical activity rates are low, and nutrition-related diseases including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension are very common or increasing rapidly.

Meanwhile, some low- and middle-income countries currently in Patterns 2–3 are facing a double burden of malnutrition, with different subpopulations experiencing undernutrition (hunger, stunting, extreme thinness) and overnutrition (increasing rates of obesity and other NCDs). Many of these countries are already seeing rapid changes in their food systems and are beginning to see the negative health consequences that follow. “Across all regions, ultra-processed food consumption is the fastest growing component of their diet — be they already in pattern 4 or just moving that way,” says Popkin.

Figure 3. Prevalence of overweight and obesity based on 1990s and late 2010s weight and height data (using UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, and NCD-RisC estimates, supplemented with selected DHS and other country direct measures). Countries colored according to highest overweight/obesity prevalence for either men or women. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13366

This outcome may not be inevitable, however. Popkin and Ng suggest that policies such as taxes on sugary drinks and junk foods, restrictions on junk food marketing, mandatory front-of-package labels, targeted food procurement and menus in schools, and incentives or subsidies for healthy foods can all help stop or reverse the ongoing shift toward-less healthy diets and increased nutrition-related disease.

There is evidence to support this from countries like Chile, where many of these policies have been implemented as part of a multi-pronged obesity prevention strategy. In addition to hiking taxes on sugary drinks in 2014, two years later Chile began requiring front-of-package warning labels on processed foods high in calories or added sugar, saturated fat, or sodium. Chile also banned promotion or sales of these products in schools and restricted marketing for them on TV and in other media. These strategies appear to be working, with observed drops in sugary drink purchases (–24%), and the amount of sodium (–37%), total calories (–24%), calories from sugar (–27%), and calories from saturated fat (–16%) Chileans bought at the store in the first year under the regulations. There is also evidence of shifting social norms and attitudes around these foods and indications that industry is responding with product reformulations.

Popkin and Ng note that meaningful national and global long-term changes will require coordinated action from multiple stakeholders, including food and beverage industry players. To date, however, industry has strongly — and often successfully — resisted efforts at serious public health regulation. “Based on experiences to date, it is clear that governments adopting and implementing these policy packages will not come without a fight from industry, particularly multinational corporations and conglomerates that now control and dominate much of our global food supply,” says Ng. “There is a need for civil society organizations and researchers to reveal these tactics and for national and multilateral institutions to ensure that their governance processes are transparent.”

“Governments adopting and implementing these policy packages will not come without a fight from industry, particularly multinational corporations and conglomerates that now control and dominate much of our global food supply.”

While the authors recognize that this can present an immense challenge, they note that the stakes are equally high. Without adopting any of the policies outlined, Popkin says, “I see within a decade all low- and middle-income countries in all continents will experience ever-growing burdens of noncommunicable diseases, including obesity.” The benefits at stake are also immense: a reduced burden of nutrition-related diseases, improved learning environments, increased productivity at work, and greater quality of life for all.

Read the full article in Obesity Reviews.

Funding provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Arnold Ventures, and NIH grant to CPC P2C HD050924; R01DK108148.